By: Dr. Rick Miner on behalf of C21 Canada

INTRODUCTION

According to David Foot and Daniel Stoffman, two internationally renowned demographers, “Demographics explain about two-thirds of everything.” (Boom, Bust & Echo, page 2). Yet, in the case of Canada’s labour market future, one might reasonably push that estimate into the 80th percentile using the 2010 and 2012 reports published by Miner, in the People Without Jobs Jobs Without People series, as the basis for the change. These reports investigated the impact of the baby boomer generation exiting the workforce resulting in significant labour force shortages.

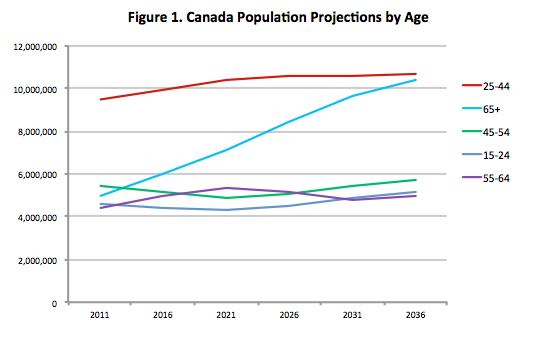

DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE

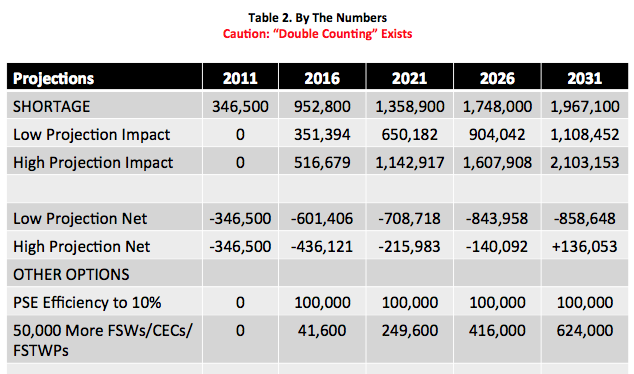

Using Statistics Canada projections, Figure 1 provides a visual image of how Canada’s demographic profile will change as the number and proportion of the population 65 and older increases while the primary working age group (25-44) remains relatively stable.

LABOUR FORCE BALANCE 2010

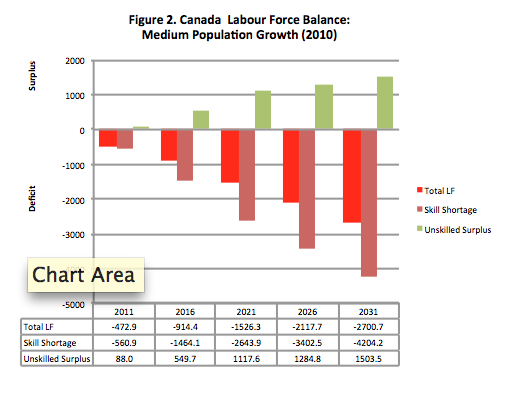

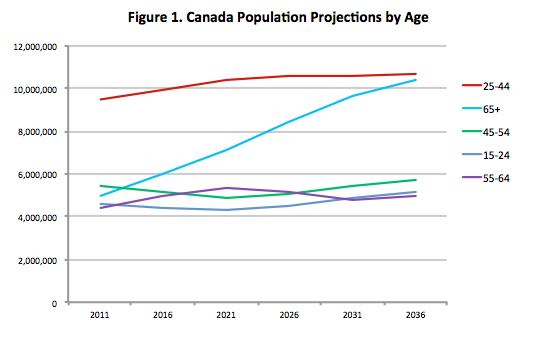

Assuming our labour force size will need to increase in rough proportion to our overall population growth, we will soon experience significant labour force shortages resulting from the fact that retired baby boomers have significantly lower labour force participation rates, and, given current trends, will not be able to be replaced fast enough by members of the younger generations.

These earlier reports projected a Canadian labour force shortage of 2.7 million and a skills shortage of 4.2 million by 2031 (Figure 2).

LABOUR FORCE BALANCE 2010

Assuming our labour force size will need to increase in rough proportion to our overall population growth, we will soon experience significant labour force shortages resulting from the fact that retired baby boomers have significantly lower labour force participation rates, and, given current trends, will not be able to be replaced fast enough by members of the younger generations.

These earlier reports projected a Canadian labour force shortage of 2.7 million and a skills shortage of 4.2 million by 2031 (Figure 2).

CHANGES SINCE 2010

Since the publication of these reports a number of dramatic shifts have occurred that warrant a re-analysis of the earlier findings. While the ultimate impact of some changes may not be known for a while, it is worth considering their implications. The changes of most significant note are:

CHANGES SINCE 2010

Since the publication of these reports a number of dramatic shifts have occurred that warrant a re-analysis of the earlier findings. While the ultimate impact of some changes may not be known for a while, it is worth considering their implications. The changes of most significant note are:

Proposed changes in retirement benefit provisions, moving eligibility from 65 to 67, should keep people in the work force longer.

Proposed changes in retirement benefit provisions, moving eligibility from 65 to 67, should keep people in the work force longer.

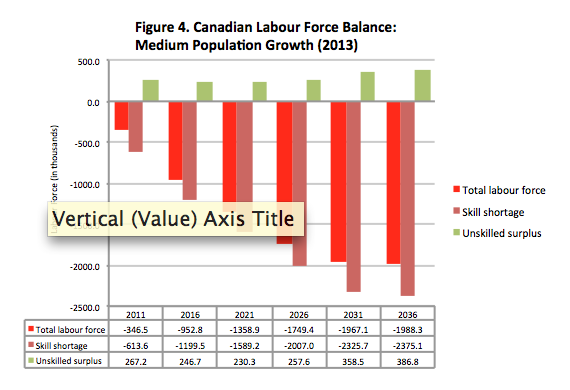

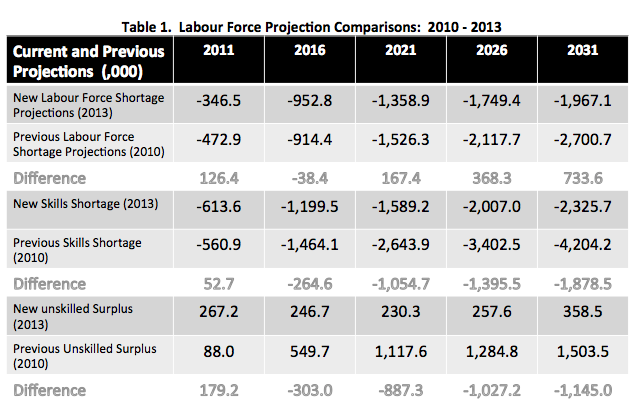

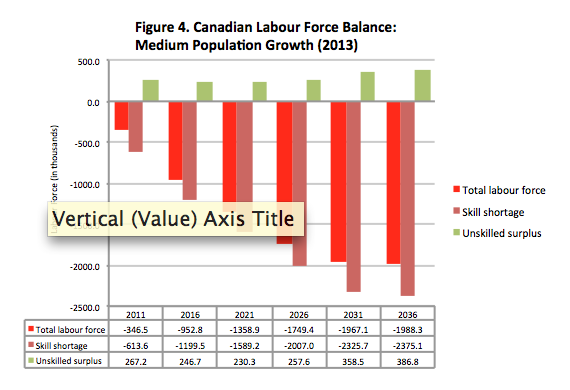

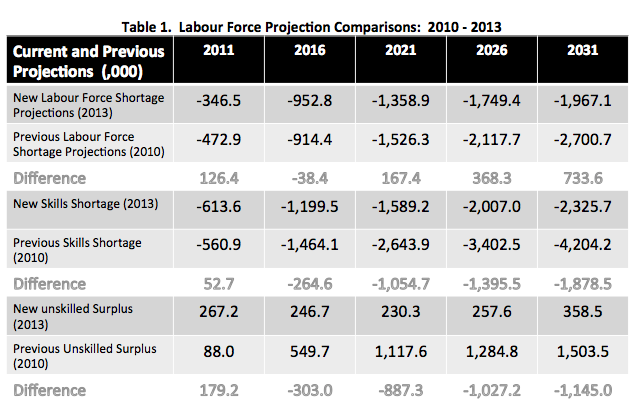

Table 1: Labour Force Projection Comparisons: 2010 -2013 provides a comparison between the earlier and this new data. The projected labour force shortages, skill shortages and projected increased levels of unemployment have improved. However, shortages still exist and they are far from trivial.

Table 1: Labour Force Projection Comparisons: 2010 -2013 provides a comparison between the earlier and this new data. The projected labour force shortages, skill shortages and projected increased levels of unemployment have improved. However, shortages still exist and they are far from trivial.

Rather than needing an additional 2.7 million workers by 2031 the shortage is now forecasted to be a little less than 2 million. Similarly, projected skills shortages drop significantly from 4.2 million to 2.3 million because of increased educational attainment levels. While the changes are encouraging, we must understand that we have major skill and labour force shortages forthcoming.

In fact, we have a two-headed problem to address in that we not only need more workers, but we need them to have the right skill sets. To increase the size of our work force, it is best to look for employment growth opportunities among those who have historically been under represented in the work force. These are immigrants, aboriginals, persons with disabilities, women, youth and older workers. Yet, we must be cognizant of the fact that these increases need to correspond to areas where skill shortages exist not in areas where there is a surplus. It was earlier assumed that simply having an educational attainment level beyond high school would be sufficient to meet businesses skill requirements. However, as will be discussed later, this assumption was far too simplistic, and will not resolve the skills mismatch problem that does and will exist.

SKILLS MISMATCH

While the debate over the existence or non-existence of a skills mismatch (skills shortage) is taking on epic proportions, many are asking a far too simplistic question (Do supply-demand mismatches currently exist?). Those on the “yes side” include IBM, Canadian Chamber of Commerce, CIBC, a majority of the sector councils, and Engineers Canada to name a few. They support their position by providing estimates showing large projected labour shortages that far exceed existing supply.

Those on the “no side”, tend to concentrate on existing economic data looking at unemployment rates compared to job vacancy rates that show significantly fewer vacancies than those who are unemployed. The assumption here is that if there were shortages then the number of job vacancies would be significantly higher, in proportional terms, to the number of unemployed. Alternatively, they look at occupations in high demand and determine the extent to which wages have increased using the hypothesis that large wage growth indicates a labour shortage (law of supply and demand). While there has been some wage growth in high demand areas the numbers have not been huge. Both approaches are fairly classical economic analysis techniques. Using them one could conclude that there is not now a labour/skills shortage.

It is less clear that these two economic approaches are able to get at the dynamics of our labour market situation for the following reasons. First, the orientation is focused more on the here and now and less so on the future. As has been shown earlier in this report (Table 1), we have experienced some short term labour force relief but our demographic reality will get progressively worse as more and more baby boomers enter retirement.

Second, a here and now analysis must consider the significant increase in the entry of temporary foreign workers to Canada, reported to be over 300,000 in 2012, which, in part, masks the labour shortage. Third, the Labour Force Participation Rate of workers 55 and older has increased which lowers the labour force shortage, which is good, but they will not stay in the work force “indefinitely”, and this reality must be considered.

Given the shortage projections provided by industry and the results of this analysis, one is inclined to accept that in 2011 there was not a major labour shortage but now (2013) one exists and evidence shows that the situation will get progressively worse. In fact, we actually have multiple skill mismatches.

These are

Rather than needing an additional 2.7 million workers by 2031 the shortage is now forecasted to be a little less than 2 million. Similarly, projected skills shortages drop significantly from 4.2 million to 2.3 million because of increased educational attainment levels. While the changes are encouraging, we must understand that we have major skill and labour force shortages forthcoming.

In fact, we have a two-headed problem to address in that we not only need more workers, but we need them to have the right skill sets. To increase the size of our work force, it is best to look for employment growth opportunities among those who have historically been under represented in the work force. These are immigrants, aboriginals, persons with disabilities, women, youth and older workers. Yet, we must be cognizant of the fact that these increases need to correspond to areas where skill shortages exist not in areas where there is a surplus. It was earlier assumed that simply having an educational attainment level beyond high school would be sufficient to meet businesses skill requirements. However, as will be discussed later, this assumption was far too simplistic, and will not resolve the skills mismatch problem that does and will exist.

SKILLS MISMATCH

While the debate over the existence or non-existence of a skills mismatch (skills shortage) is taking on epic proportions, many are asking a far too simplistic question (Do supply-demand mismatches currently exist?). Those on the “yes side” include IBM, Canadian Chamber of Commerce, CIBC, a majority of the sector councils, and Engineers Canada to name a few. They support their position by providing estimates showing large projected labour shortages that far exceed existing supply.

Those on the “no side”, tend to concentrate on existing economic data looking at unemployment rates compared to job vacancy rates that show significantly fewer vacancies than those who are unemployed. The assumption here is that if there were shortages then the number of job vacancies would be significantly higher, in proportional terms, to the number of unemployed. Alternatively, they look at occupations in high demand and determine the extent to which wages have increased using the hypothesis that large wage growth indicates a labour shortage (law of supply and demand). While there has been some wage growth in high demand areas the numbers have not been huge. Both approaches are fairly classical economic analysis techniques. Using them one could conclude that there is not now a labour/skills shortage.

It is less clear that these two economic approaches are able to get at the dynamics of our labour market situation for the following reasons. First, the orientation is focused more on the here and now and less so on the future. As has been shown earlier in this report (Table 1), we have experienced some short term labour force relief but our demographic reality will get progressively worse as more and more baby boomers enter retirement.

Second, a here and now analysis must consider the significant increase in the entry of temporary foreign workers to Canada, reported to be over 300,000 in 2012, which, in part, masks the labour shortage. Third, the Labour Force Participation Rate of workers 55 and older has increased which lowers the labour force shortage, which is good, but they will not stay in the work force “indefinitely”, and this reality must be considered.

Given the shortage projections provided by industry and the results of this analysis, one is inclined to accept that in 2011 there was not a major labour shortage but now (2013) one exists and evidence shows that the situation will get progressively worse. In fact, we actually have multiple skill mismatches.

These are

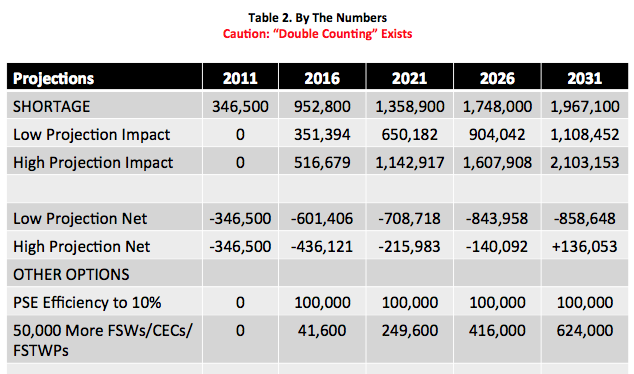

To achieve this would necessitate success in implementing the new immigration programs, improving aboriginal LFPRs to the national average by 2031, reducing the LFPR gap for persons with disabilities by 25% by 2031, reducing the female LFPR gap by 50% by 2031, achieving LFPRs for older workers equal to the current United States averages by 2026, and improving post-secondary efficiencies by 5% by 2016.

The labour force shortfall could be reduced to almost a breakeven point if we were to increase our immigration quota by 50,000, concentrating on younger better skilled workers.

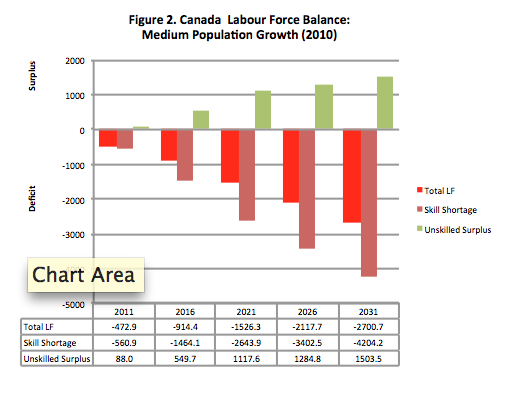

Table 2: By the Numbers also shows the impact of more aggressive objectives in each area of interest. Admittedly these changes will not be automatic and will require some investments, but we need to make them or the consequences will be dire.

RECOMMENDATIONS

So our numerical shortage is solvable but we still need to avoid the skills mismatches by having more of the right people with the right skills in the right place at the right time. To do this, to get the right skill matches, we need to make a number of significant changes. Of particular note are the following:

To achieve this would necessitate success in implementing the new immigration programs, improving aboriginal LFPRs to the national average by 2031, reducing the LFPR gap for persons with disabilities by 25% by 2031, reducing the female LFPR gap by 50% by 2031, achieving LFPRs for older workers equal to the current United States averages by 2026, and improving post-secondary efficiencies by 5% by 2016.

The labour force shortfall could be reduced to almost a breakeven point if we were to increase our immigration quota by 50,000, concentrating on younger better skilled workers.

Table 2: By the Numbers also shows the impact of more aggressive objectives in each area of interest. Admittedly these changes will not be automatic and will require some investments, but we need to make them or the consequences will be dire.

RECOMMENDATIONS

So our numerical shortage is solvable but we still need to avoid the skills mismatches by having more of the right people with the right skills in the right place at the right time. To do this, to get the right skill matches, we need to make a number of significant changes. Of particular note are the following:

LABOUR FORCE BALANCE 2010

Assuming our labour force size will need to increase in rough proportion to our overall population growth, we will soon experience significant labour force shortages resulting from the fact that retired baby boomers have significantly lower labour force participation rates, and, given current trends, will not be able to be replaced fast enough by members of the younger generations.

These earlier reports projected a Canadian labour force shortage of 2.7 million and a skills shortage of 4.2 million by 2031 (Figure 2).

LABOUR FORCE BALANCE 2010

Assuming our labour force size will need to increase in rough proportion to our overall population growth, we will soon experience significant labour force shortages resulting from the fact that retired baby boomers have significantly lower labour force participation rates, and, given current trends, will not be able to be replaced fast enough by members of the younger generations.

These earlier reports projected a Canadian labour force shortage of 2.7 million and a skills shortage of 4.2 million by 2031 (Figure 2).

CHANGES SINCE 2010

Since the publication of these reports a number of dramatic shifts have occurred that warrant a re-analysis of the earlier findings. While the ultimate impact of some changes may not be known for a while, it is worth considering their implications. The changes of most significant note are:

CHANGES SINCE 2010

Since the publication of these reports a number of dramatic shifts have occurred that warrant a re-analysis of the earlier findings. While the ultimate impact of some changes may not be known for a while, it is worth considering their implications. The changes of most significant note are:

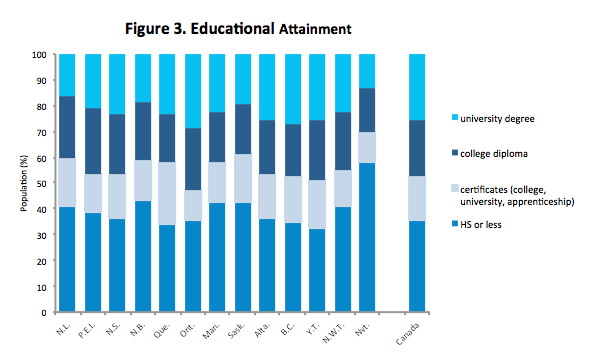

- Labour force participation rates for those 55 and older have increased (largely attributed to our recent economic difficulties).

- The Federal Government has established a number of new immigration programs (Canadian Experience Class, Foreign Skilled Trade Worker Program and the Foreign Skilled Worker Program) targeting younger immigrants who have employment skills and/or Canadian education and training specifically geared to our labour market needs which should increase their labour force participation rates.

- Labour Force demand projections have decreased.

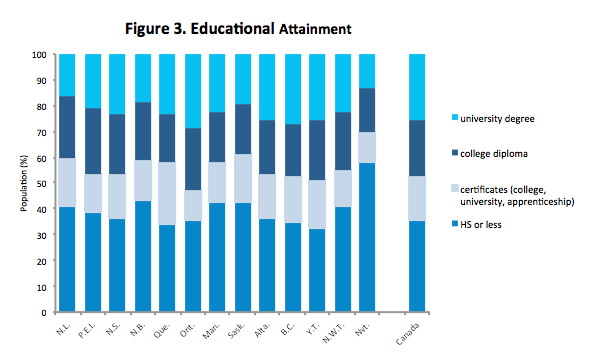

- Recent Statistics Canada data, using 2011 census results, show Canada has achieved educational attainment levels higher than previously projected (Figure 3).

Proposed changes in retirement benefit provisions, moving eligibility from 65 to 67, should keep people in the work force longer.

Proposed changes in retirement benefit provisions, moving eligibility from 65 to 67, should keep people in the work force longer.

- New investments have been made in increasing the educational opportunities for aboriginals and persons with disabilities which should result in a larger and more skilled work force.

Table 1: Labour Force Projection Comparisons: 2010 -2013 provides a comparison between the earlier and this new data. The projected labour force shortages, skill shortages and projected increased levels of unemployment have improved. However, shortages still exist and they are far from trivial.

Table 1: Labour Force Projection Comparisons: 2010 -2013 provides a comparison between the earlier and this new data. The projected labour force shortages, skill shortages and projected increased levels of unemployment have improved. However, shortages still exist and they are far from trivial.

Rather than needing an additional 2.7 million workers by 2031 the shortage is now forecasted to be a little less than 2 million. Similarly, projected skills shortages drop significantly from 4.2 million to 2.3 million because of increased educational attainment levels. While the changes are encouraging, we must understand that we have major skill and labour force shortages forthcoming.

In fact, we have a two-headed problem to address in that we not only need more workers, but we need them to have the right skill sets. To increase the size of our work force, it is best to look for employment growth opportunities among those who have historically been under represented in the work force. These are immigrants, aboriginals, persons with disabilities, women, youth and older workers. Yet, we must be cognizant of the fact that these increases need to correspond to areas where skill shortages exist not in areas where there is a surplus. It was earlier assumed that simply having an educational attainment level beyond high school would be sufficient to meet businesses skill requirements. However, as will be discussed later, this assumption was far too simplistic, and will not resolve the skills mismatch problem that does and will exist.

SKILLS MISMATCH

While the debate over the existence or non-existence of a skills mismatch (skills shortage) is taking on epic proportions, many are asking a far too simplistic question (Do supply-demand mismatches currently exist?). Those on the “yes side” include IBM, Canadian Chamber of Commerce, CIBC, a majority of the sector councils, and Engineers Canada to name a few. They support their position by providing estimates showing large projected labour shortages that far exceed existing supply.

Those on the “no side”, tend to concentrate on existing economic data looking at unemployment rates compared to job vacancy rates that show significantly fewer vacancies than those who are unemployed. The assumption here is that if there were shortages then the number of job vacancies would be significantly higher, in proportional terms, to the number of unemployed. Alternatively, they look at occupations in high demand and determine the extent to which wages have increased using the hypothesis that large wage growth indicates a labour shortage (law of supply and demand). While there has been some wage growth in high demand areas the numbers have not been huge. Both approaches are fairly classical economic analysis techniques. Using them one could conclude that there is not now a labour/skills shortage.

It is less clear that these two economic approaches are able to get at the dynamics of our labour market situation for the following reasons. First, the orientation is focused more on the here and now and less so on the future. As has been shown earlier in this report (Table 1), we have experienced some short term labour force relief but our demographic reality will get progressively worse as more and more baby boomers enter retirement.

Second, a here and now analysis must consider the significant increase in the entry of temporary foreign workers to Canada, reported to be over 300,000 in 2012, which, in part, masks the labour shortage. Third, the Labour Force Participation Rate of workers 55 and older has increased which lowers the labour force shortage, which is good, but they will not stay in the work force “indefinitely”, and this reality must be considered.

Given the shortage projections provided by industry and the results of this analysis, one is inclined to accept that in 2011 there was not a major labour shortage but now (2013) one exists and evidence shows that the situation will get progressively worse. In fact, we actually have multiple skill mismatches.

These are

Rather than needing an additional 2.7 million workers by 2031 the shortage is now forecasted to be a little less than 2 million. Similarly, projected skills shortages drop significantly from 4.2 million to 2.3 million because of increased educational attainment levels. While the changes are encouraging, we must understand that we have major skill and labour force shortages forthcoming.

In fact, we have a two-headed problem to address in that we not only need more workers, but we need them to have the right skill sets. To increase the size of our work force, it is best to look for employment growth opportunities among those who have historically been under represented in the work force. These are immigrants, aboriginals, persons with disabilities, women, youth and older workers. Yet, we must be cognizant of the fact that these increases need to correspond to areas where skill shortages exist not in areas where there is a surplus. It was earlier assumed that simply having an educational attainment level beyond high school would be sufficient to meet businesses skill requirements. However, as will be discussed later, this assumption was far too simplistic, and will not resolve the skills mismatch problem that does and will exist.

SKILLS MISMATCH

While the debate over the existence or non-existence of a skills mismatch (skills shortage) is taking on epic proportions, many are asking a far too simplistic question (Do supply-demand mismatches currently exist?). Those on the “yes side” include IBM, Canadian Chamber of Commerce, CIBC, a majority of the sector councils, and Engineers Canada to name a few. They support their position by providing estimates showing large projected labour shortages that far exceed existing supply.

Those on the “no side”, tend to concentrate on existing economic data looking at unemployment rates compared to job vacancy rates that show significantly fewer vacancies than those who are unemployed. The assumption here is that if there were shortages then the number of job vacancies would be significantly higher, in proportional terms, to the number of unemployed. Alternatively, they look at occupations in high demand and determine the extent to which wages have increased using the hypothesis that large wage growth indicates a labour shortage (law of supply and demand). While there has been some wage growth in high demand areas the numbers have not been huge. Both approaches are fairly classical economic analysis techniques. Using them one could conclude that there is not now a labour/skills shortage.

It is less clear that these two economic approaches are able to get at the dynamics of our labour market situation for the following reasons. First, the orientation is focused more on the here and now and less so on the future. As has been shown earlier in this report (Table 1), we have experienced some short term labour force relief but our demographic reality will get progressively worse as more and more baby boomers enter retirement.

Second, a here and now analysis must consider the significant increase in the entry of temporary foreign workers to Canada, reported to be over 300,000 in 2012, which, in part, masks the labour shortage. Third, the Labour Force Participation Rate of workers 55 and older has increased which lowers the labour force shortage, which is good, but they will not stay in the work force “indefinitely”, and this reality must be considered.

Given the shortage projections provided by industry and the results of this analysis, one is inclined to accept that in 2011 there was not a major labour shortage but now (2013) one exists and evidence shows that the situation will get progressively worse. In fact, we actually have multiple skill mismatches.

These are

- Supply-demand mismatches which tends to be the focus of the current debate.

- A geographical mismatch (skills in the wrong place) which is becoming increasingly evident as mega projects emerge (oil sands in Alberta, LNG terminals in Northern BC, mine expansions in BC, the Yukon and Ontario, natural resource projects in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, energy projects in Labrador and Quebec, ship building in Vancouver, Halifax and Montreal, and an Eastern pipeline headed to Saint John, NB).

- An underemployment (over skilled) reality particularly among our youth. A recent study by the Certified General Accounts of Canada found that 24.5% of recent university graduates were underemployed. A similar study in the United States found the rate to be 48%.

- Finally, we have another mismatch where the skills of the workers are less than those required of their positions (under skilled/overemployment).

To achieve this would necessitate success in implementing the new immigration programs, improving aboriginal LFPRs to the national average by 2031, reducing the LFPR gap for persons with disabilities by 25% by 2031, reducing the female LFPR gap by 50% by 2031, achieving LFPRs for older workers equal to the current United States averages by 2026, and improving post-secondary efficiencies by 5% by 2016.

The labour force shortfall could be reduced to almost a breakeven point if we were to increase our immigration quota by 50,000, concentrating on younger better skilled workers.

Table 2: By the Numbers also shows the impact of more aggressive objectives in each area of interest. Admittedly these changes will not be automatic and will require some investments, but we need to make them or the consequences will be dire.

RECOMMENDATIONS

So our numerical shortage is solvable but we still need to avoid the skills mismatches by having more of the right people with the right skills in the right place at the right time. To do this, to get the right skill matches, we need to make a number of significant changes. Of particular note are the following:

To achieve this would necessitate success in implementing the new immigration programs, improving aboriginal LFPRs to the national average by 2031, reducing the LFPR gap for persons with disabilities by 25% by 2031, reducing the female LFPR gap by 50% by 2031, achieving LFPRs for older workers equal to the current United States averages by 2026, and improving post-secondary efficiencies by 5% by 2016.

The labour force shortfall could be reduced to almost a breakeven point if we were to increase our immigration quota by 50,000, concentrating on younger better skilled workers.

Table 2: By the Numbers also shows the impact of more aggressive objectives in each area of interest. Admittedly these changes will not be automatic and will require some investments, but we need to make them or the consequences will be dire.

RECOMMENDATIONS

So our numerical shortage is solvable but we still need to avoid the skills mismatches by having more of the right people with the right skills in the right place at the right time. To do this, to get the right skill matches, we need to make a number of significant changes. Of particular note are the following:

- We need to drastically improve our Labour Market Information System. The movement to the National Household Survey appears to have had a negative effect on the validity of our data given the significantly lower response rate (68% to 93%). Even without this problem, we face poor educational achievement data which makes it impossible to accurately tie educational attainment to economic outcomes. This makes it difficult to know what resources we have available and how much we need.

- We need a national education and training strategy. To assume that all provinces will engage in educational and training initiatives that are in the best interest of the country is somewhere between naïve and simplistic. The original federal-provincial agreement around educational responsibilities in 1867 had little to do with the value of post-secondary education but rather the role of religion. Being the only G-7 country without a national education strategy should be instructive.

- Career Counselling, assuming we have some good data to convey, should be “mandatory” for all high school students (perhaps even earlier), their parents, teachers and administrators. In addition, it should be used and widely available at colleges, universities and polytechnics.